The Subjective Theory of Value

Economist Carl Menger’s theory of value is one of the most significant breakthroughs in the history of economics.

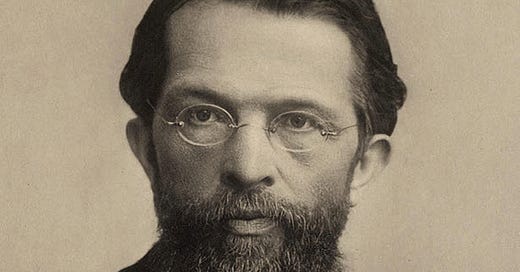

Carl Menger was a nineteenth-century Austrian economist and is considered the founder of the Austrian School of Economics. He changed economics forever, and for the better, by starting the marginal utility revolution. He developed the theory of marginalism- that individuals decide to buy goods and services based on the utility that additional units purchased will provide. Individuals make economic decisions at the margins. Out of the Marginalist Revolution comes the subjective theory of value- goods and services don’t have inherent value from inputs of labor and other resources. The subjective, intertemporal, and ever-changing individual preferences of human minds determine the value of goods and services. That’s what markets are. This article will concentrate on these theories and attempt to highlight their remarkable beauty that led to the creative destruction that swept away other lesser theories of value.

Before the subjective theory of value became the standard in modern economics, there was the labor theory of value (LTV). Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations, posits the theory of value with LTV. It’s one of the few major flaws in his economic theories that didn’t stand the test of time like much of the rest of The Wealth of Nations. Division of labor, specialization, free exchange markets, comparative advantage, and the primacy of the growth of a nation’s productivity for the benefit of all of its citizens have been hallmarks of developed economies since Adam Smith and why he’s known as the person who wrote the most important and famous economics book ever written. Adam Smith published the Wealth of Nations in 1776. That was the same year the American Colonies issued the Declaration of Independence. Sparks of revolution abound. Time’s illuminating gift of hindsight has given us plenty of years to test his theories. Even someone as brilliant as Adam Smith can commit an error on a critical idea in a subject as vastly complex and delicate as economics. Economics is delicate because all economic theories can be butchered and turned into monsters if not correctly formulated, tested, and proven beyond any doubt to the public.

Commodities turn into goods and services from the production inputs of labor. Smith connected those two dots and concluded that the value of goods and services came from labor. He thought the nominal price(market price) of goods and services reflected the natural price (intrinsic value) that labor produced. When you stop and think about it, this makes sense. A car takes a lot more labor to produce than a hammer, so of course, it costs more. Building a house, even if you exclude the land it’s on, takes much more labor than building what’s inside the house, such as cabinets, flooring, doors, Etc. So it should cost more, and it does. LTV makes even more sense in the time, place, and audience to which Smith spoke: Late 18th century Europe during the age of Enlightenment and the onset of productive industry in cities. He argued for capitalistic free trade as countries were evolving out of mercantilist economics. Mercantilism measured a nation’s wealth in gold and silver. It meant conquest and all the horribleness that came along with it. Trade policy sought to maximize a country’s exports while barring its imports. In mercantile economic systems, noble landowners made their money off workers on their lands. Smith correctly saw that the productive powers of urban-centered industry and unhindered exchange and trade were vastly superior in every imaginable way to this medieval agrarian economic system.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a crucial measurement used today to measure a nation’s wealth. How we got there comes from one of Adam Smith’s key insights- the productive powers and capabilities of the labor of a country. Against this backdrop, it’s easy to see why Smith thought the value of goods and services came from the work it took to make them. It appeared to fit into place. Smith spoke of the value of goods and services, labor’s role in the productive processes to them, and how that relates to their price in a marketplace.

Another economist and philosopher also believed in the Labor Theory of Value, which stood as a basis for many of his ideas. Except the conclusions and solutions he drew from it were radically different. His name was Karl Marx, someone not typically associated with Adam Smith. Marx was formulating his ideas on workers overthrowing capitalists and needed persuasive economic theories to push forward. He took LTV and opined that if value comes from labor, then labor is the most crucial factor in the means of production. “The existing relations of capital,” as he put it, meant that capitalists exploited the surplus labor out of workers for profit. The real value of society belonged to labor alone, and it was being stolen away from workers by capitalists (proletarians against the bourgeoisie) in an ongoing class struggle that explained the human development of history. Marx meant for his view of the labor theory of value to have nothing to do with a marketplace, and it was a revolutionary call for the workers to seize the means of production.

Marx was wrong on LVT, and Menger proved it. Smith and classical economists like David Ricardo were the original ones who made an error on LVT. Menger, at last, set the record straight on value. He did this by showing a phenomenon in economic laws. There is no such thing as actual intrinsic value in goods and services. Any real production inputs (land, labor, and capital) are not alone measurable. Value begins and ends in the individual’s mind and what they are willing to pay for a good or service. Prices are the nominal abstraction of an individual’s beliefs about what something is worth. Marx’s interpretation of LVT is nonsense on purely empirical grounds. There is no value in labor by itself. Value comes only in the demand of buyers for products and services.

Hold a product you want to buy in your right hand. Then, hold up a product you don’t want to buy with your left hand. There isn’t anything with intrinsic value in your left hand because of the labor it took to make. As far as you are concerned, the thing in your left hand is worthless. It has a market price, as do all goods and services, but that doesn’t mean it is intrinsically worth anything to you. You can’t presume to tell others that that item in your left hand has intrinsic worth. It’s up to them to figure out for themselves what is valuable. In reality, labor gets its value when it makes goods and services people want to buy in a marketplace. It’s through people’s willingness to purchase goods and services that labor gets its value. Labor should get more gains in the productive processes of a market economy through the direct action of unions and negotiation with capital. All value comes from productivity to meet demand- buyers’ desires and preferences in markets. Goods and services are not constants valued only once by individuals. They are variables moving through time and space and are valued differently and subjectively by individuals and firms. Exchange isn’t zero-sum. Both sides can profit from the exchange. Price movements in marketplaces are abstract reflections of complex information that measure what a buyer is willing to pay at that moment.